Reverse Engineering Crazy Taxi, Part 1

For some reason I put Crazy Taxi into the browser and You Can Too

For some reason I put Crazy Taxi into the browser and You Can Too

From time to time, and usually in the winter, a certain madness takes hold of me. Cooped up indoors from nasty weather and depressing grey vistas, I’ll sink my teeth into an unreasonably sized engineering task and usually not let go for months. My friends have dubbed this my strange moods, named after a phenomenon in the game Dwarf Fortress where dwarves will stop whatever they are doing and pursue the construction of some ornate artifact, usually to the exclusion of everything else.

This year, my winter madness project was adding the classic game Crazy Taxi to noclip.website, my friend Jasper’s insanely cool and ambitious project. You can click here to check it out, and use WASD and your mouse to freely fly around the levels of the game. noclip calls itself a “digital museum of video game levels”, and I think that’s a great way to summarize its goal: it allows users to freely explore, in the browser, 3D recreations of hundreds of maps from dozens of video games ranging from the N64 era to relatively modern PC games, while also representing an open source recreation of each of those games’ original rendering methods.

That’s because one of Jasper’s rules for contributions to the site is that each added game must operate using the game’s original files; no Blender exports, no pre-processing with modding tools, just rendering the game from its original files, all in the browser. That means adding a game to noclip involves effectively reverse engineering and recreating major portions of that game’s code, from custom parsers for bespoke file formats, to rendering loops which often resemble the original game engine, to occasionally recreating parts of the game’s AI and mechanics (seriously, check out the Bullet Bills in Super Mario Galaxy’s Buoy Base Galaxy level; you might just find an easter egg).

So before we move on, I highly recommend taking a minute to explore the various games and levels on noclip. There’s a seriously good chance that the site has at least one game you adore, and getting to freely fly around the 3D spaces you might’ve last experienced as a child is an amazing experience. It should also hopefully communicate the scope of what adding a game to the site entails!

Back to my winter madness. In previous years I contributed two fairly large games to noclip, Halo and World of Warcraft, so I was fairly familiar with the process of reverse engineering a game and writing a renderer for it. However, for both of those games there already existed substantial modding communities and copious amounts of technical documentation for how the games worked, down to detailed byte-level diagrams of each file format. This made it more approachable (though definitely not easy) to write those games’ renderers, and I owe those communities a huge debt of gratitude for their documentation efforts.

But this year, I wanted to try something new: I decided I’d add a game to noclip that wasn’t already understood, didn’t already have the secrets of its file formats neatly displayed on a community wiki, and that didn’t have any tools already for viewing its maps. And, thanks largely to my recent acquisition of a Flippy Drive for my GameCube, I recently became re-enamored with Crazy Taxi, and thus my fate was sealed.

And so, this blog post (or more likely series of posts) is going to be a whirlwind tour of how I reverse engineered Crazy Taxi from (mostly) scratch, and created a renderer for it in noclip. This won’t really be a tutorial on noclip.website development as such, though we will talk a bit about how my renderer works. Instead, my goal here is to describe the process of reversing in a way that is instructive, so that someone with a basic grasp of programming and maybe some 3D graphics chops can easily follow along, and hopefully feel like they too could’ve reversed the game. Wherever possible, I’ll try to stick to the actual sequence of events leading to the game being on noclip, pointing out the lessons I learned along the way. Also, since Jasper was a close advisor during this whole process, I’ll be sure to point out whenever something was a suggestion or addition from him.

So, you’ve decided to reverse engineer Crazy Taxi. That’s great! But which version of Crazy Taxi are we talking about? After all, the game was first released for arcade cabinets in 1999, then was ported to the Sega Dreamcast in 2000, then to Sony PlayStation 2 and Nintendo GameCube in 2001, then to the PC in 2002, then to iOS in 2012, and Android in 2013. Many of these ports were done by different studios and use different proprietary file formats, engines, and were written for totally different computer architectures. So which game are we talking about here?

Because I’d been playing the GameCube version of the game, and since Jasper has developed something of a toolkit for GameCube games on noclip, I was naturally inclined towards that version. However, as Jasper pointed out, the Android version was apparently shipped with its debug symbols, which would make reverse engineering it substantially easier. And while this Android version may prove useful to us later, it was the GameCube version that I ended up opting for, so I acquired a disc image ROM of the game.

Let’s take a second to talk about our tools. While I’m by no means prescriptive of this, there are some tools that are pretty standard for reverse engineering for good reason:

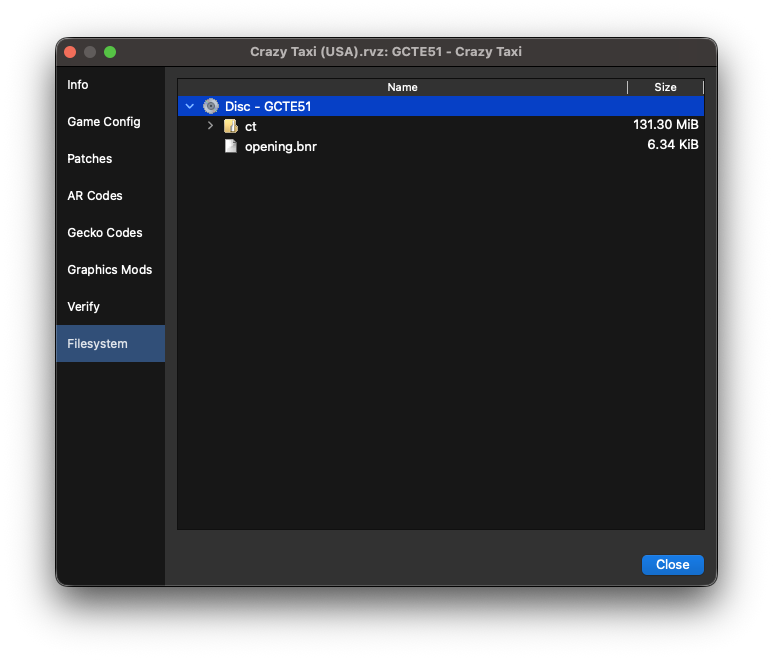

At last, we’re ready to start looking at some bytes. The Crazy Taxi ROM I have, Crazy Taxi (USA).rvz, is about 90MB, which is considerably smaller than the average GameCube ROM at 1.4GB. While I could load this up into a hex editor and get to sleuthin’, I happen to already know that .rvz is a file format used by the Dolphin project as a more compact alternative to .iso, another disc image format. And luckily, Dolphin has tools for opening and extracting these: set the ROM’s directory as Dolphin’s game directory, right-click on the game and select Properties, then click on the Filesystem tab:

From here, you can right-click on “Disc 1 - GCTE51”, and then extract the entire disc somewhere on your computer. Great, now we’re actually able to read some game data!

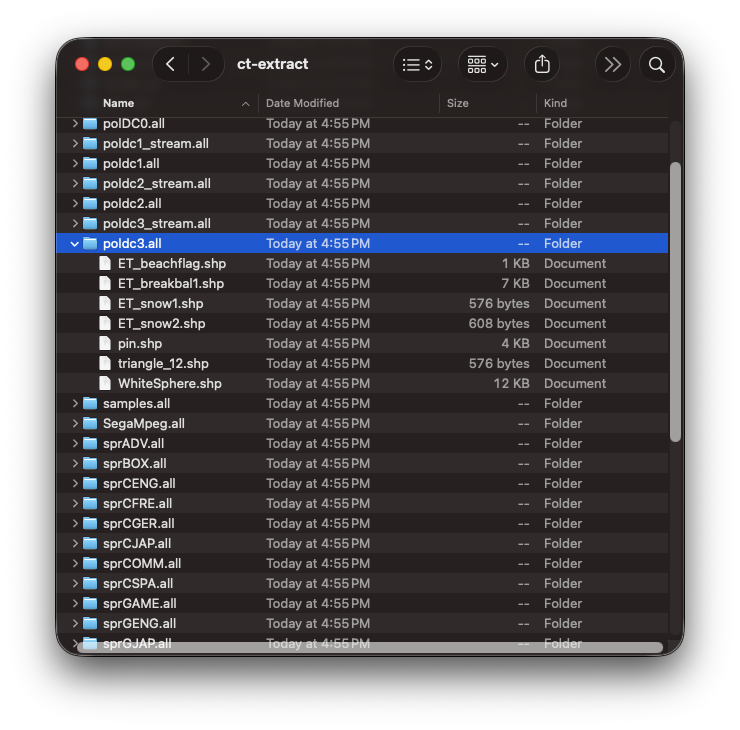

Let’s see what we’re working with here:

$ tree ct-extract/

ct-extract/

├── files

│ ├── ct

│ │ ├── aklmmpeg.all

│ │ ├── arial12.fnt

│ │ ├── colDC1.bin

│ │ ├── colDC2.bin

│ │ ├── colDC3.bin

│ │ ├── courrier32.fnt

│ │ ├── CT.txt

│ │ ├── ctlogoL.wav

│ │ ├── ctlogoR.wav

│ │ ├── cube0.shp

│ │ ├── Files.tmp

│ │ ├── landac

│ │ │ ├── land01.tex

│ │ │ ├── ...

│ │ │ └── land33.tex

│ │ ├── landac.all

│ │ ├── landdc

│ │ │ ├── land01.tex

│ │ │ ├── ...

│ │ │ └── land29.tex

│ │ ├── landdc.all

│ │ ├── legalscr.tex

│ │ ├── misc.all

│ │ ├── misc.lst

│ │ ├── motDC.bin

│ │ ├── music

│ │ │ ├── alliwant.adp

│ │ │ ├── ...

│ │ │ └── waydown.adp

│ │ ├── objDC1.bin

│ │ ├── objDC2.bin

│ │ ├── objDC3.bin

│ │ ├── polDC0.all

│ │ ├── poldc1_stream.all

│ │ ├── poldc1.all

│ │ ├── poldc2_stream.all

│ │ ├── poldc2.all

│ │ ├── poldc3_stream.all

│ │ ├── poldc3.all

│ │ ├── recAdvAC.bin

│ │ ├── recAdvDC.bin

│ │ ├── recEndAC.bin

│ │ ├── recEndDC.bin

│ │ ├── samples.all

│ │ ├── SegaMpeg.all

│ │ ├── sizes.dat

│ │ ├── sizes.txt

│ │ ├── splDC1.bin

│ │ ├── splDC2.bin

│ │ ├── splDC3.bin

│ │ ├── sprADV.all

│ │ ├── ...

│ │ ├── sprTSPA.all

│ │ ├── texDC0.all

│ │ ├── texDC1.all

│ │ ├── texDC2.all

│ │ ├── texdc3.all

│ │ ├── TEXTURE.tex

│ │ ├── voice_a.all

│ │ ├── voice_b.all

│ │ ├── voice_c.all

│ │ ├── voice_d.all

│ │ ├── voices.all

│ │ └── white.tex

│ └── opening.bnr

└── sys

├── apploader.img

├── bi2.bin

├── boot.bin

├── fst.bin

└── main.dol

7 directories, 148 files

I took some liberties in abbreviating the listing here, but besides a couple .wav and .txt files, there’s a whole lotta file extensions I don’t recognize. Googling them doesn’t really get us anywhere either, which leads me to think these are proprietary files designed by the GameCube port’s developer, Acclaim.

While we don’t know yet what these files are, we can certainly make some educated guesses about the purposes of some of them. .tex sure sounds like it’s probably used for textures, .shp kinda resembles the word “shape”, so maybe it has to do with polygon data. And in the suspiciously named music/ directory, we have a couple .adp files that have the names of the songs in the game, so maybe they’re audio files? Googling “audio adp file”, I found this resource, which checks out.

These .all files look the most promising to me, though, since they comprise the majority of the game’s data (outside the binary itself), so let’s start there.

.all.all as an extension name is pretty vague, but based on the wide variety of filenames using it (e.g. voices.all, texDC0.all, polDC0.all), we might guess it’s some sort of general purpose file format. Here’s the first couple hundred bytes of the smallest of these, files/ct/poldc3.all:

If you’ve never looked at data in a hex editor before, here’s a quick tour of what what’s going on here. In the middle, we have the file contents of poldc3.all in hexadecimal form, followed by an ASCII representation of the same data (with a dim grey . representing unprintable ASCII characters). Running down the left column are the file offsets into poldc3.all where each line of bytes occurs. And on the bottom, we have a panel which shows different interpretations of the currently selected data: as signed & unsigned integers of various bit lengths, and as a 16-bit and 32-bit floating point numbers. Finally, there’s a toggle on whether to interpret the data as big-endian or little-endian. You can click on any byte (or ASCII character) to select a 4-byte sequence for interpretation.

Something that’s immediately evident here is there appear to be filenames of .shp files at regular intervals, along with some other non-ASCII values. If you click around the editor, you can get a sense of what these values might represent, even if we don’t yet know their actual format. For example, assuming little-endian values (I’ll get back to endianness in a second), the first value looks like it’s almost certainly the integer 7 since the floating point values are way too small to be likely candidates. And, wouldn’t you know it, there happen to be 7 filenames following it, followed by some data that seems to break from the pattern. This hints us towards a first testable theory about the file: the first number in an .all file might represent how many filenames follow it.

As for which endianness to choose, there’s a long and a short answer here. The short answer is I usually toggle between the two until values start looking “reasonable”, i.e. values around the order of magnitude I’d expect for a game. Let’s save the long answer for later, since this will come up again soon, but for now we’ll stick with little-endian since that seems to work best for this data.

Back to our theory about the first number. To see if it holds any water, let’s check out the first kilobyte or so of another relatively small .all file, files/ct/sprCENG.all:

Once again, we have a pretty unambigious integer value starting at the first byte, and this time it’s 0x13, or 19 in decimal, which again matches the number of strings we see immediately following it. That said, we still aren’t sure whether that first integer is 8 bits, 16 bits, or 32 bits long. But a pattern is definitely emerging! Checking a few more files, I see this pattern holds even for very large .alls, and also notice that the first four bytes is never occupied with anything except for this integer value. This leads me to update our theory: the first four bytes is an unsigned 32-bit (4-byte) integer representing the number of filenames following it.

At this point, because I’ve reverse engineered a number of file formats before, I’ve also made a guess as to the purpose of .all files: they represent some kind of archive file that can contain a number of other named files, sort of like a tarball.

Archive files are common in video games for the same reason they’re common in lots of contexts where many files are read: I/O is expensive! If you can frontload operations that take a long time, like loading a bunch of related files from a spinning disc, it’s easier to guarantee reliably fast operations on that data later. And importantly, archive file formats tend to start with some kind of table of contents which lists their constituent files, as well as some info on where to find them, such as offsets to their start/end, or their length. Since that seems to be what we’re looking at, let’s see if we can determine the format of our table of contents.

Looking at our two example .alls, we can see that after the first four bytes the same pattern of values occurs: 20004100, followed by 8 null bytes. Checking a bunch of other .alls, it seems they all share this pattern, so it doesn’t seem to vary based on the number of filenames or any other factor. Since they seem to be constant, let’s ignore them for now. Finally, at offset 0x10, we see our first filename.

Now, for sprCENG.all, we know our archive contains 19 files, so in addition to the 19 filenames, we’d also expect to find that many values describing how to find them. These values might be interleaved with the filenames, or might be listed as their own contiguous array. Looking at our data, there is a suspicious non-ASCII value that’s interleaved between filenames, so I think we’re looking at an array of filename/value pairs. And when we have an array of structures like this, a good first step is to figure out whether the elements are of fixed or variable length.

If they were variable length, we’d expect to see another integer value describing how long each item is, but I don’t see anything like that. Instead, just eyeballing the data, it looks like these items are all the same length!

To find that fixed length, just try counting the number of bytes from the start of the first filename (ST_mode_s_eng01.tex) to the start of the second (ST_mode_s_eng01b.tex): 68 bytes. And, indeed, checking the distance from the second to the third filename is also 68 bytes. Seems we have another theory: each table of contents item is 68 bytes long.

Looking at any 68 byte chunk, it seems there’s not much going on besides the filename and the few non-ASCII bytes at the end. Similar to our analysis of the entire item, we might note that the strings don’t have a length value associated with them, so let’s assume they’re also a fixed length of 64 bytes (i.e. all but the last 4 bytes). This would be consistent with a fairly common pattern when dealing with fixed-length blocks of data: they tend to have lengths that are powers of 2.

With all this in mind, we now have enough of a working theory to write our first parser!

This may feel premature, since we still don’t know what half of these values are, and we haven’t even touched the other 80% of the data in the file. But writing a parser, even an incomplete one, is a crucial step towards testing the theories we have so far, and running it on our entire set of data will tell us much more than eyeballing the data ever could.

So, let’s codify what we suspect about the .all format into some pseudocode structs:

struct ArchiveHeader {

u32 num_files,

u16 unk0, // "unk" is a common abbreviation of "unknown"

u16 unk1,

u8 empty[8],

TableOfContentsEntry toc[num_files],

}

struct TableOfContentsEntry {

char filename[64],

u32 unk0,

}If you’re unfamiliar with C-like struct syntax, what we’re describing here is the layout of our file’s data. You can see we’ve placed the 4-byte unsigned int number of filenames at the start, followed by our as-yet unknown 20004100 sequence followed by 8 null bytes, and then an array of our filename/number pair structs.

Also, note that even though we don’t know what many of these fields are, we’ve still given them types and placeholder names which we can update later as we learn more.

In my actual code, I use a lovely little Rust library called deku which lets me write the entire binary parser using structs and declarative macros like this:

#[derive(DekuRead, Debug)]

pub struct ArchiveHeader {

n_items: u32,

unk0: u16,

unk1: u16,

#[deku(pad_bytes_before = "8", count = "n_items")]

toc: Vec<TableOfContentsEntry>,

}

#[derive(DekuRead, Debug)]

pub struct TableOfContentsEntry {

#[deku(count = "64")]

filename: Vec<u8>,

unk0: u32,

}From this, deku generates a parser implementation, allowing me to simply call something like ArchiveHeader::from_bytes(data) to parse the entire header.

Finally, we can test our theory by simply running the parser on every .all file we’ve got. As it turns out, it prints out exactly what we’d expect with no panics! But you can imagine how if we saw some garbage characters in filename, or parsed a value of 12,000,000 for n_items, that might indicate we’ve gone astray somewhere. This brings us to a really significant lesson I’ve learned while reverse engineering: as early as humanly possible, test your theories with actual code. I can’t tell you how much time I’ve wasted by working based on untested assumptions, only to find out they were wrong hours later.

unk statusAnyway, since it seems we’re on the right track, let’s figure out what the unk0 field in TableOfContentsEntry represents by taking another look at poldc3.all:

Recall that a table of contents entry should either include either an offset to the data start, the size of the data, or possibly both. Using our parser, let’s print out what each of the 7 TableOfContentsEntry values are:

| filename | unk0 (in decimal) |

|---|---|

| ET_beachflag.shp | 1312 |

| pin.shp | 4160 |

| ET_breakbal1.shp | 7456 |

| ET_snow1.shp | 576 |

| ET_snow2.shp | 608 |

| WhiteSphere.shp | 12128 |

| triangle_12.shp | 576 |

If unk0 represented an offset into the file, I’d expect one of these to be close to where we know the header data stops, which is around 0x1F0 (or 496), but none are. Also, we should never see two values with the same offset, since that’d mean two files contain the same data, yet ET_snow1.shp and triangle_12.shp have the same value. So we can probably rule offsets out.

So let’s assume the alternative, that unk0 represents the byte size of each file. Then the sum of the values should equal the size of the entire file minus the size of the header.

Unfortunately, if we run the numbers, we find that things don’t exactly line up:

| Name | Size (bytes) |

|---|---|

| `ArchiveHeader` | 492 |

| Sum of all `unk0` values | 26816 |

| `ArchiveHeader` + `unk0` values | 27308 |

| Total file size | 27328 |

We’re off by… just 20 bytes??? Clearly something in our theory is wrong, which isn’t necessarily surprising — in reverse engineering, your guesses are going to be wrong a lot. But on the other hand, our theory’s prediction is off by just a fraction of 1%, which means we shouldn’t throw our unk0-as-file-size theory out the window entirely. Instead, let’s see if we can figure out where this 20 byte gap is coming from.

My first thought when dealing with this gap was to revisit our ArchiveHeader struct to see if I missed an “offset to the start of the actual data” type value. Finding nothing, I instead took a closer look at the end of poldc3.alls header data. At the end of our TableOfContentsEntry list, at offset 0x1E8, we see triangle_12.shps unk0 value of 40020000. Then, we see exactly 20 more null bytes before the first non-null data appears again.

Although this looks very promising, it might just be a coincidence, and we need more information to identify whether it’s a pattern.

.shp of things to comeFirst, it would help if we knew what data a .shp file is supposed to start with, since that would help us find any other gaps between .shp file data. Although the first couple bytes of our .all archives represent the number of files they contain, and thus can vary from archive to archive, it’s fairly common for file formats to start with the same constant value for ease of identification. This is often called a file’s magic number, and is a great heuristic for identifying what a random blob of data might represent.

Luckily, we have a single loose .shp specimen from our extracted ROM to compare against: files/ct/cube0.shp, and it’s small enough that I can include it in its entirety here:

Now there’s plenty of interesting bits in here, and we’ll be revisiting this file in much greater detail in a later post, but for now just take note of the first 4 bytes of the file. When Jasper saw this, he said something along the lines of “ah 3f800000, what a classic,” as if he were greeting an old friend, to which I very reasonably replied asking what the hell he was talking about.

Read as a big endian 32 bit floating point number, 3f800000 is 1.0, which is a value that comes up a lot in game data. Having spent years doing this, Jasper identified it immediately and guessed that since it was at the start of the file, this might represent a version number for the .shp file format, which could give us a great candidate for a magic number to look for.

And yes, we have now switched to interpreting data as big endian instead of little endian. To be honest, I don’t have a great explanation for why the folks at Acclaim use little endian for their .all headers and big endian elsewhere. I do know that GameCube runs on a PowerPC architecture, which is big endian, but that doesn’t explain why the .all headers are little. Jasper theorized that perhaps files that are meant to be marshalled directly into C structs were serialized as big endian, while data that was meant to be parsed incrementally like the .all header is little, but unfortunately we just have to roll with the punches on this one.

Now, if we revisit poldc0.all, sure enough the very first non-null sequence of bytes after the end of our header is 3f800000 at offset 0x200. And while I only include the first couple hundred bytes in this post’s hex editor, if you were able to advance 492 bytes forward from there (which, you may recall, corresponds to the length of our first TableOfContentsEntry), you’d end up on another 3f800000 value. This pattern of advancing by the unk0 value and landing on another f32 1.0 value holds for the rest of the file.

So this tells us that after the first 20 byte gap, it seems that all of poldc0.all files are contiguous, and their sizes are described by unk0. At this point, even if we’re not totally sure about the 20 byte gap, I think we can safely rename TableOfContentsEntry.unk0 to TableOfContentsEntry.file_size.

#[derive(DekuRead, Debug)]

pub struct TableOfContentsEntry {

#[deku(count = "64")

filename: Vec<u8>,

file_size: u32, // no longer unknown!

}So why is the gap 20 bytes, and is it the same in other .all files? Well, if we check sprCENG.all, the gap between the end of its last file_size value and the first non-null byte is 6 bytes, though it’s worth noting that sprCENG.all contains .tex files, and we don’t have a good sense of how they begin yet.

Since we only have a good handle on the .shp headers right now, let’s instead take a survey of the .all archives that only contain .shps. Because we know how to print out the constituent filenames of any .all file, this is pretty easy to do, and it turns out all of the files named poldc*.all or poldc*_stream.all contain just .shps. So let’s take a closer look at their header/data gaps:

| Filename | Offset to end of ArchiveHeader | Offset to first `1.0` | Gap size (bytes) |

|---|---|---|---|

| polDC0.all | 0x1A558 | 0x1A560 | 8 |

| poldc1_stream.all | 0x7930 | 0x7940 | 16 |

| poldc1.all | 0x1660 | 0x1660 | 0 |

| poldc2_stream.all | 0x5840 | 0x5840 | 0 |

| poldc2.all | 0x27A4 | 0x27C0 | 28 |

| poldc3_stream.all | 0x2298 | 0x22A0 | 8 |

| poldc3.all | 0x1EC | 0x200 | 20 |

It turns out the gap varies considerably, ranging from 0 bytes to 28. This is interesting, but what stood out to me were the offsets where the first 1.0 occurs. Note that they always end in a 0, unlike the offsets to the end of our ArchiveHeader. This means that their offset are always multiples of 0x10, or 16! And if you look a bit more closely, you might notice their 2nd digits are always even — this implies they’re actually all multiples of 0x20, or 32. This may seem like a subtle or arbitrary observation, but it’s actually a very common pattern when laying out data called alignment.

Data is often aligned to multiples of some number of bytes, sometimes referred to as its alignment boundary. This happens for a number of reasons depending on the application, but generally it’s to improve runtime performance at the expense of storage size. In this case, it’s hard to say exactly why the data is aligned to 0x20 byte boundaries, but it’s possible it’s due to the GameCube’s cache size.

With this observation, we can make a final theory about how .all files are formatted: each archived file’s data is together starting at the nearest 0x20 byte boundary following the header.

.all togetherNow at last, using the theories we’ve built up so far, we can write some pseudocode that extracts files from an .all archive, and dumps the constituent files into a directory with the same name:

archive_data = read_file(archive_name)

// parse the header

header = ArchiveHeader.parse(archive_data)

// advance to the end of the header section

pos = sizeof(header)

// align to the nearest 0x20 byte boundary

if pos % 0x20 != 0:

pos += 0x20 - (pos % 0x20)

// read off each file's data

for entry in header.toc:

start = pos

end = pos + entry.file_size

file_data = archive_data[start..end]

write_file(archive_name + "/" + entry.filename, file_data)

pos += file_sizeIf you’d like to see the non-pseudo version of my archive reader, you can check out my Rust implementation here. Running a real Rusty version of the above, we end up with all of the game files extracted neatly into their archive directories:

I think that’s where I’ll leave us for part 1. I realize it’s pretty anticlimactic to stop before we’ve even rendered anything, but considering we started with nothing but an illegible ROM file, having access to each and every game file is actually a pretty substantial accomplishment!

Next time, we’ll revisit our old friend cube0.shp and attempt to decode the mysteries of the .shp file to draw our first game model.